20 Years of the WLDS gene

Article posted: 19th November, 2021

20 Years of the WLDS gene: the real life story

Text by Professor Michael Coleman

Illustrations by Dr Alice White

Global crisis and the ECR

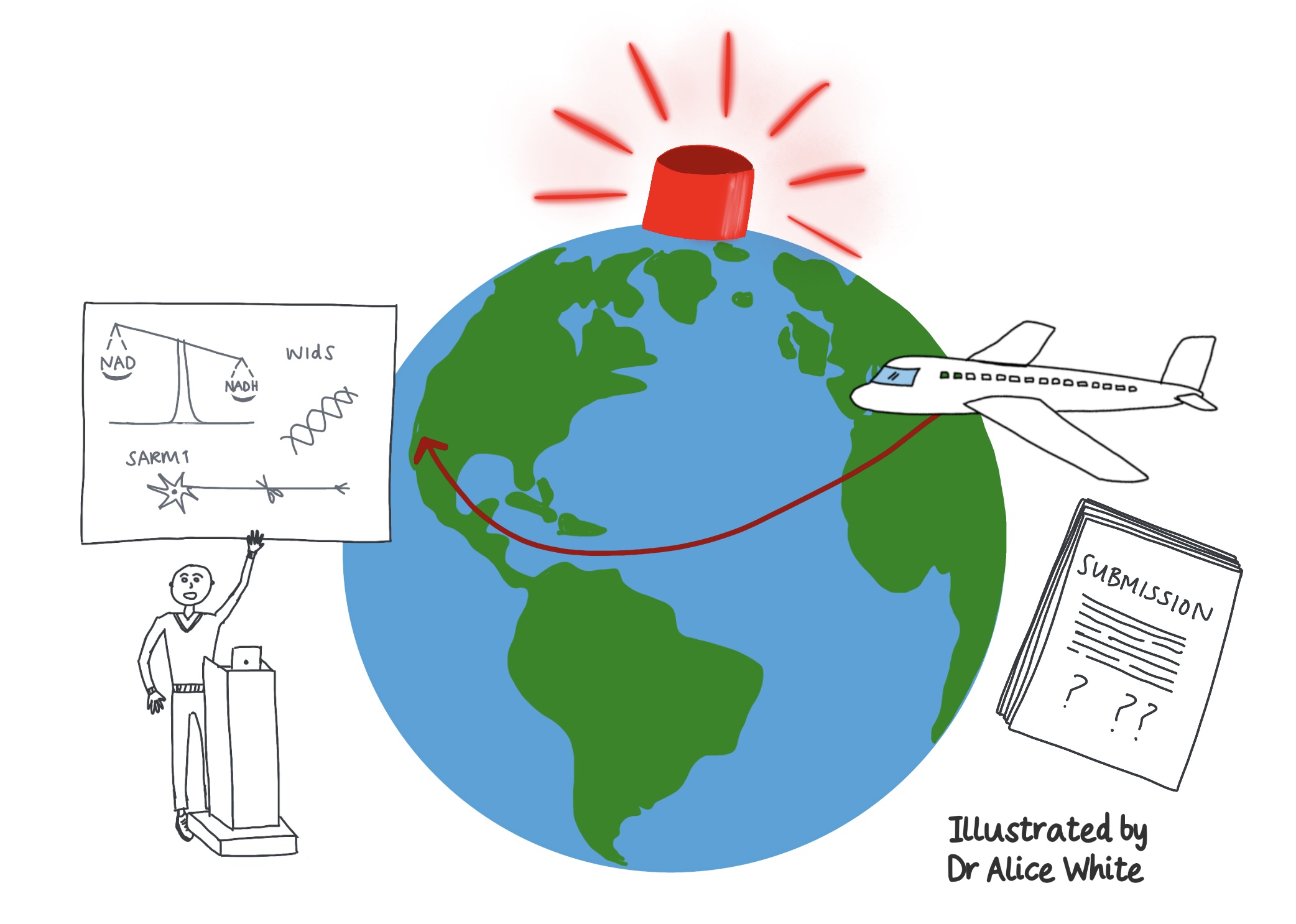

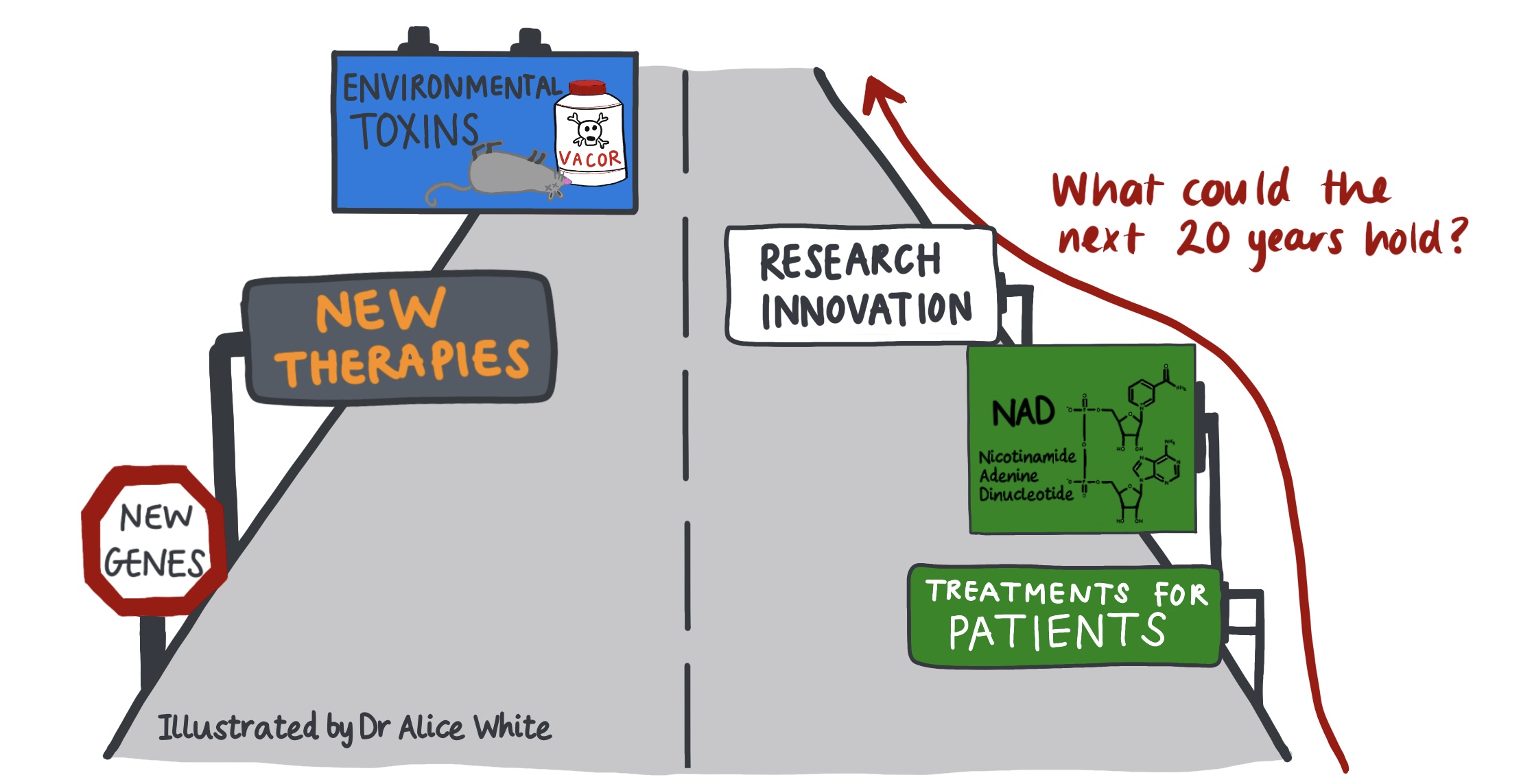

20 years ago today, 19th November, 2001, as an early career researcher (ECR) in Cologne, I led a team that published the first gene showing NAD metabolism strongly influences axon degeneration. This finding began today’s detailed understanding of programmed axon death.

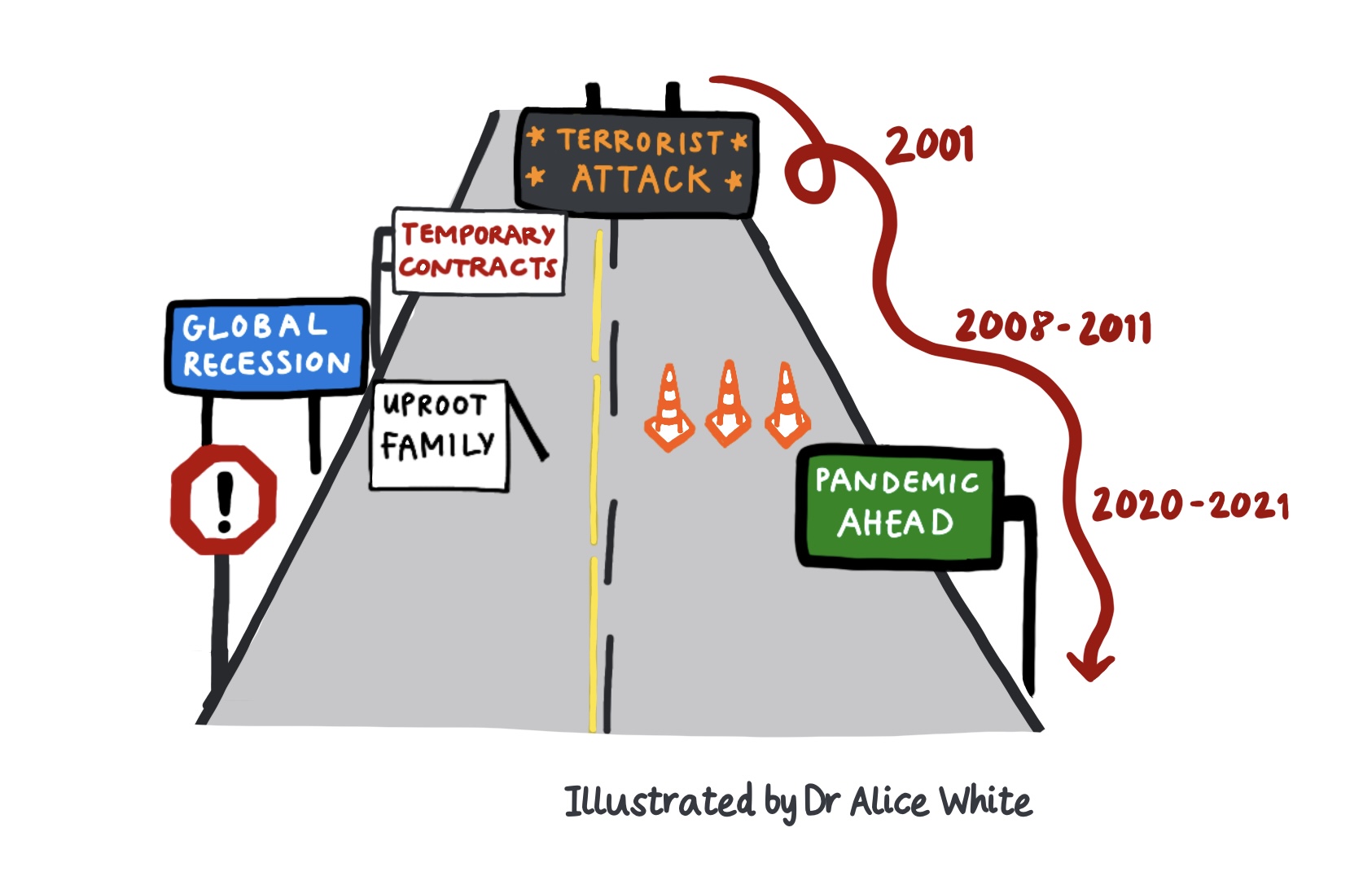

I planned to mark this anniversary only with a scientific update. But as I reflected on the intervening years, and the coincidence of yet another global crisis each decade, it struck me what valuable lessons this story holds for today’s ECRs. It’s tough, struggling to maintain research in a global crisis while temporary funding ticks away, but this is a story that shows it can be done and reminds us all that while these events may last a while, they also end and steadily research builds to a far bigger story.

One day, years from now, you may be able to reassure your own students and postdocs that ups and downs, even bizarre ones, are not so unusual. That even in a global pandemic there was job mobility, research did eventually restart and, with resilience and flexibility, careers could be forged.

But I do hope this story inspires you to watch also the accompanying short science video: the 20 year journey from intriguing new gene to detailed molecular pathway, human gene mutations [1,2,3], complete rescue of disease [4,5], and worldwide drug discovery efforts [6,7].

Terrorism: November 2001

The September 11th attacks were fresh in everyone’s minds. The personal tragedies were of course the worst part. Closer to home, my wife and I had an inquisitive two-year-old son. Where could we even start to explain if he began asking us “why?”, as two-year-olds do. But in our research team we had another concern – trivial in comparison but definitely important to us. That paper my research group had sent for review, the culmination of 7 years of research and our biggest discovery yet, was in New York on that day. These were the days of analogue review, when you couriered five printed copies across the Atlantic, each with glossy figures on expensive paper. This was already our fourth submission and we needed it published soon.

How close was the Nature Neuroscience office to the World Trade Center? Had we really come through two desk rejections, an appeal, and two tough rounds of review only for our paper to be caught up in this?

I had planned to attend the SFN meeting in San Diego in November. Was it safe to fly? My post as a junior PI in Cologne was temporary. If these attacks sparked a global recession, how would I find the next job? Who would invest in science when the wars started?

The answers: The wars came and international tensions worsened for years, but there was no recession yet, and eventually there was some kind of stability. The paper hadn’t been close to the attacks, it was accepted, I did go to SFN (definitely the right decision – I have always made so many important contacts there), and the research grew and grew. I moved to a supposedly secure position at the Babraham Institute near Cambridge, and our son, now almost four, had a baby brother.

Recession: November 2011

First the good news. He had a sister too. I had “tenure” – just as well with those responsibilities. We’d learned a lot about how the gene we discovered protects axons. Our work, and that of Marc Freeman and colleagues, had revealed the two proteins that today are believed to form the central core of the Wallerian degeneration pathway: NMNAT2 and SARM1. We knew nothing yet about how they talk to one another but that was soon to follow. There was much to be pleased about.

And the bad news? Ironically, the days of late 2011 were the darkest in my career. The 2008 financial crisis sparked years of government cuts and in November 2011 the axe randomly swung our way. After achieving several breakthroughs, after hauling my family twice across Europe, after building up a thriving group, I was forced to spend a year doing little but defend its existence. However, we did survive, at the cost of a lot of stress and no small thanks to the unswerving support of Institute Director, Michael Wakelam, Programme Lead, Len Stephens, and the incredible tolerance and talents of my students and postdocs.

So now the questions began again: was I really going to go through that process another time in the next five-yearly review? Can a PI truly mentor and develop their postdocs and students when they are made to fight for their own career, no matter how successful they had been? And could the clinical relevance of our research be better exploited elsewhere?

The answers: No, no and yes.

Pandemic: November 2021

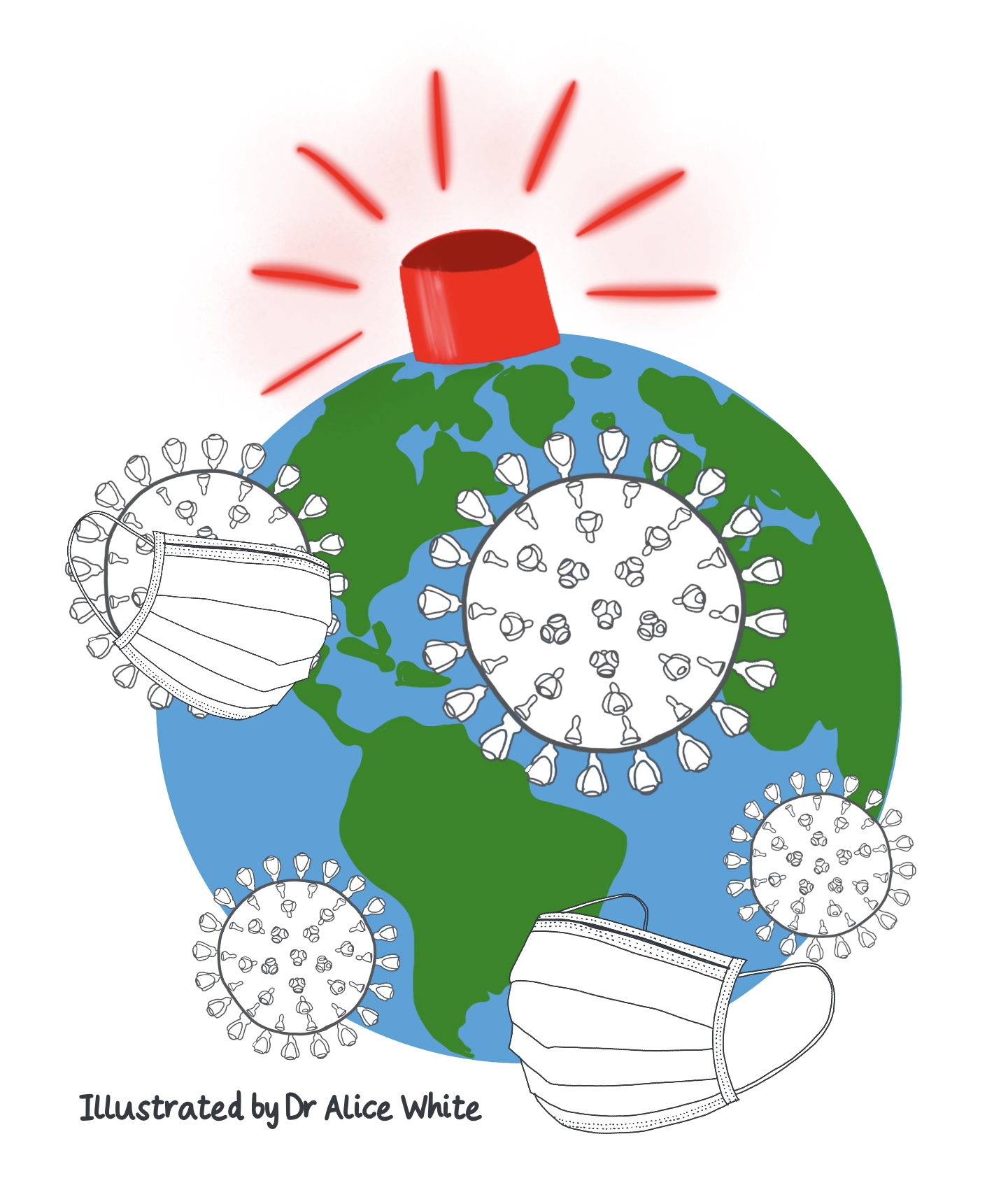

Six years into a now truly secure position, I’m loving the real leadership, mentoring and wider thinking this frees me up to do. It’s not all rosy of course. The pandemic has been highly disruptive for everyone.

Those career uncertainties that no longer plague me are now those of my postdocs, students and kids, and when they get the knocks it still hurts. Also our grants and papers still get rejected – everyone gets that. The biological clock doesn’t tick forever, and who knows what the next global shock will be and how we all get through it?

More intriguingly though, who knows where the research will lead? None of us sees more than a short way ahead, however much we, our funders and “big” journals would like to think we do. All we do know is that the next 20 years will bring equally massive progress, with more highly unexpected twists and a lot of excitement.

And for all its difficulties and uncertainties, through whatever the world throws at us, that’s what keeps us in research!