Article by Prof Michael Coleman; illustrations by Dr Alice White

Your stomach falls as you open the email: “Thank you for your submission to Journal X …after careful consideration and discussion with senior colleagues, we regret to inform you…insufficient strength of advance…not of general interest…incremental...”

Years of hard research and it’s a desk rejection by the editor. They didn’t even send your work for peer review. You can’t bring yourself to read the rest, even the usual platitudes about your high quality work and its suitability for more specialist journals.

If you’re an early career researcher (ECR), you briefly despair about your future. If you’re an established PI, you worry about wasting your life - all those years of research experience - on such an inefficient process. After a period of fuming, from hours to days, you shrug and mutter something about: “least-worst system” and “can’t change it”. You start looking for the next highest impact factor journal.

But is it true? Who decides your work is ‘incremental’? Is there really no better way? And do you really have no influence?

Who decides?

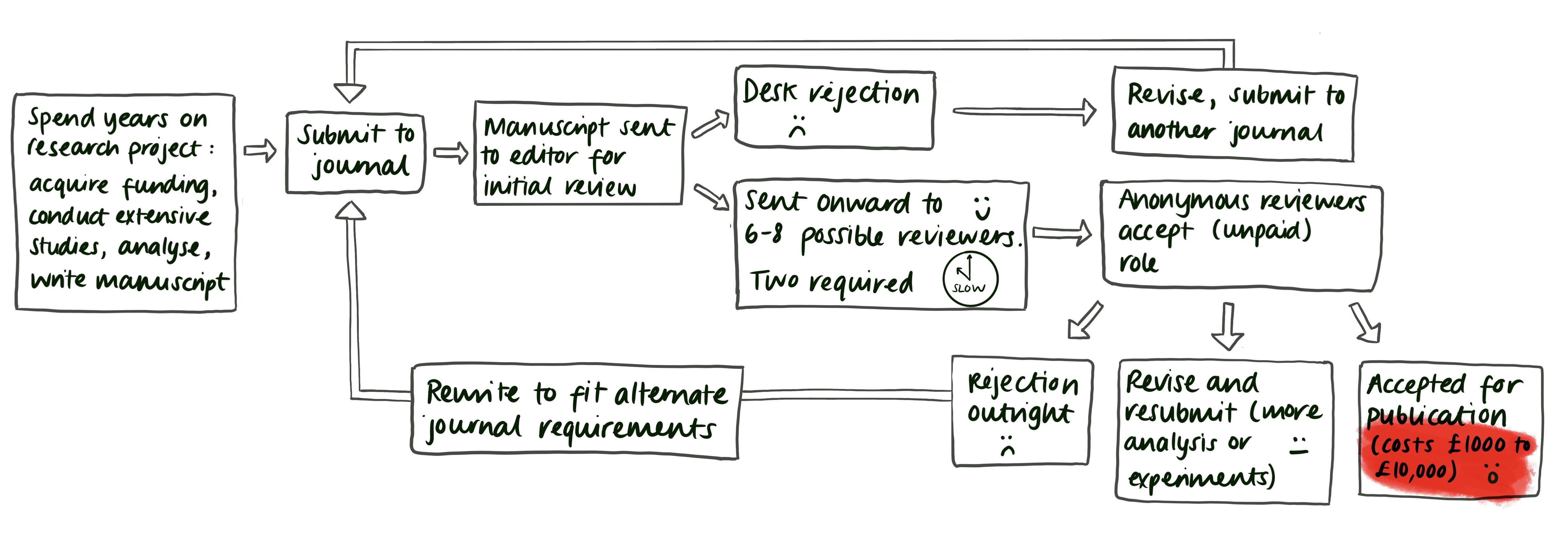

Handling editors make most initial decisions at ‘big’ journals. These are mostly former postdoc level researchers. Senior colleagues may contribute but have very limited time for most papers. So relatively junior staff, often under pressure to protect profit margins, have major influence over researchers’ careers, over future funding prospects, and over which research becomes ‘high profile’. That’s a big ask for someone whose own research experience may be less than your postdoc’s.

Shocking imbalance

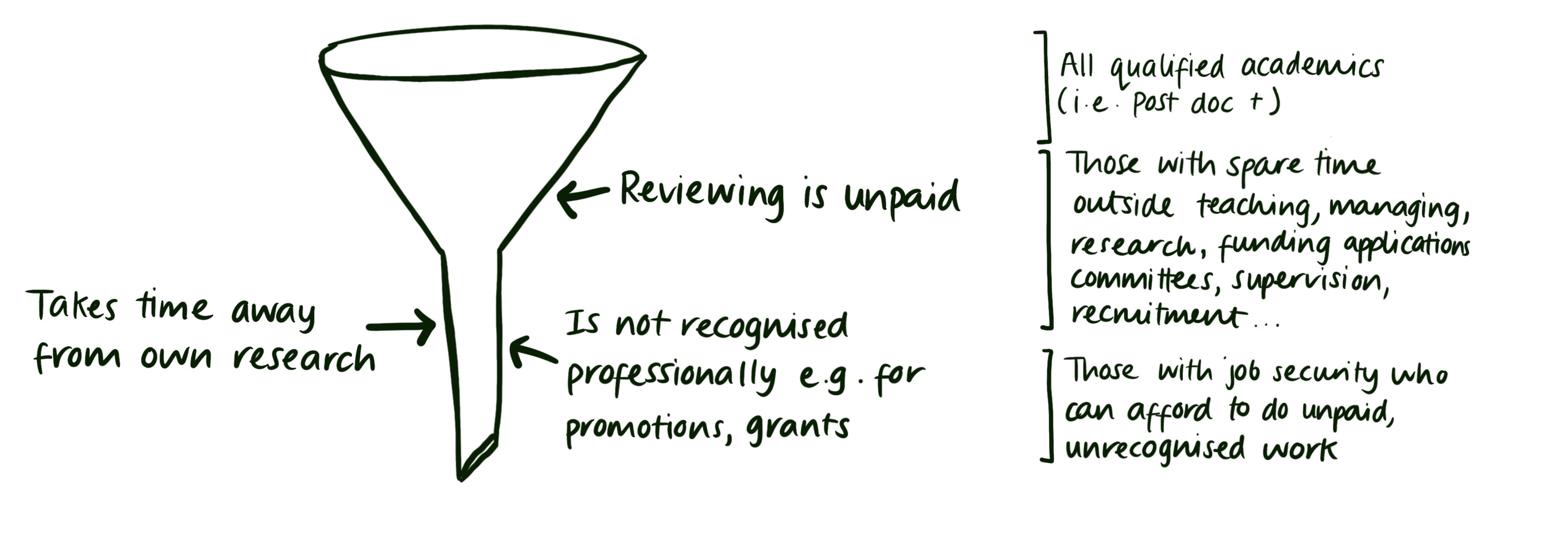

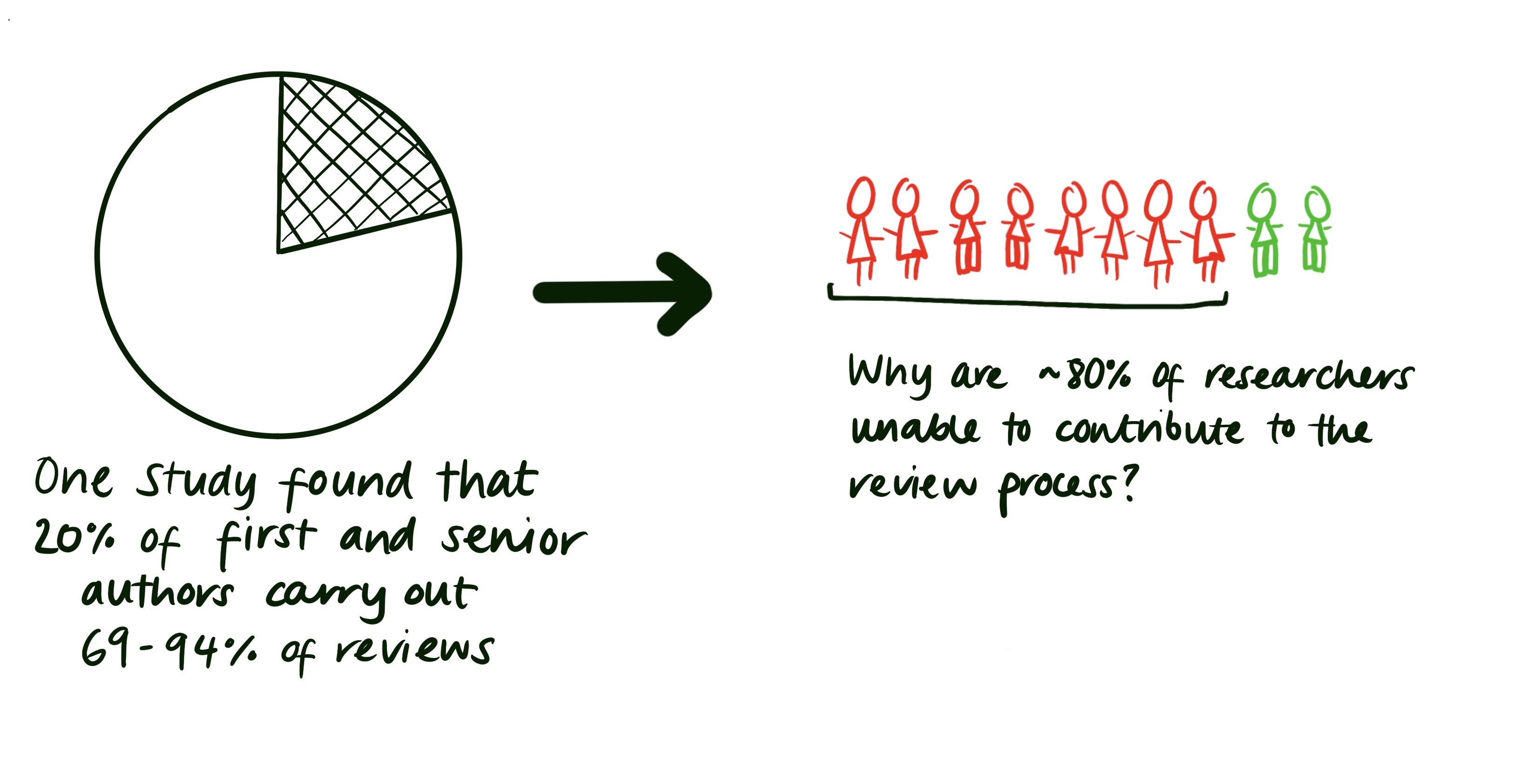

Peer review is usually an anonymous process, so you can’t see whether everyone contributes. But from the limited data available, one study found just 20% of first or senior authors carried out 69-94% of reviews.

If this is replicated across research, just consider what it means:

- A huge imbalance of workload

- An unrepresentative reviewer pool

- Reviewers assessing work far from their area of expertise

- Difficulty for editors to find reviewers

Editors often ask 6-8 scientists to find two reviewers. Desk rejections lower this significant workload and its cost, but to be clear: desk rejection is not peer review.

Hope and inevitability

The world around our science bubble has not stood still. Journals once had vital roles in printing the literature, distributing, indexing and peer reviewing it. Now only the last remains, and often not even that. Overuse of desk rejection threatens the entire peer review model.

But just as the Internet has disrupted how we shop, watch movies, hold meetings, and even find a partner, it has transformed every aspect of science publishing bar one: peer review. Why would this stop now?

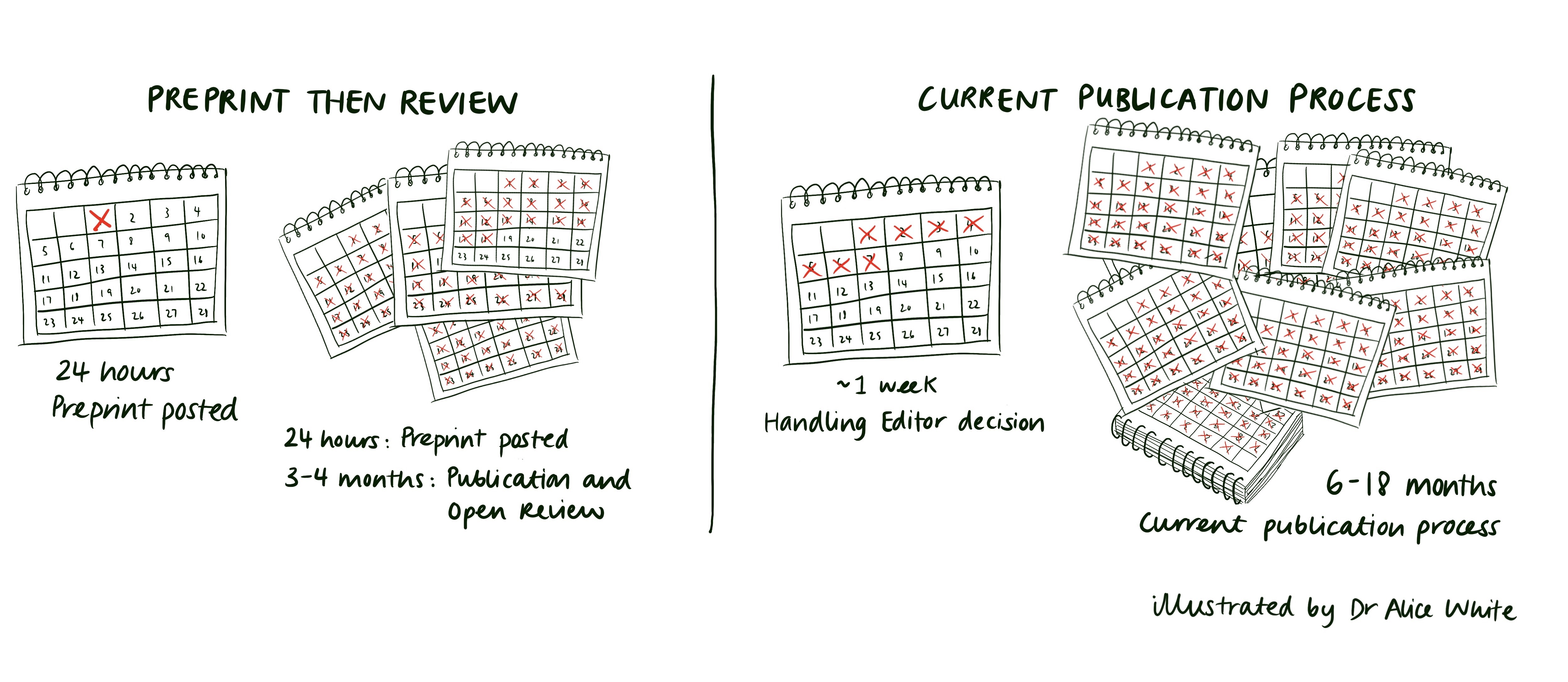

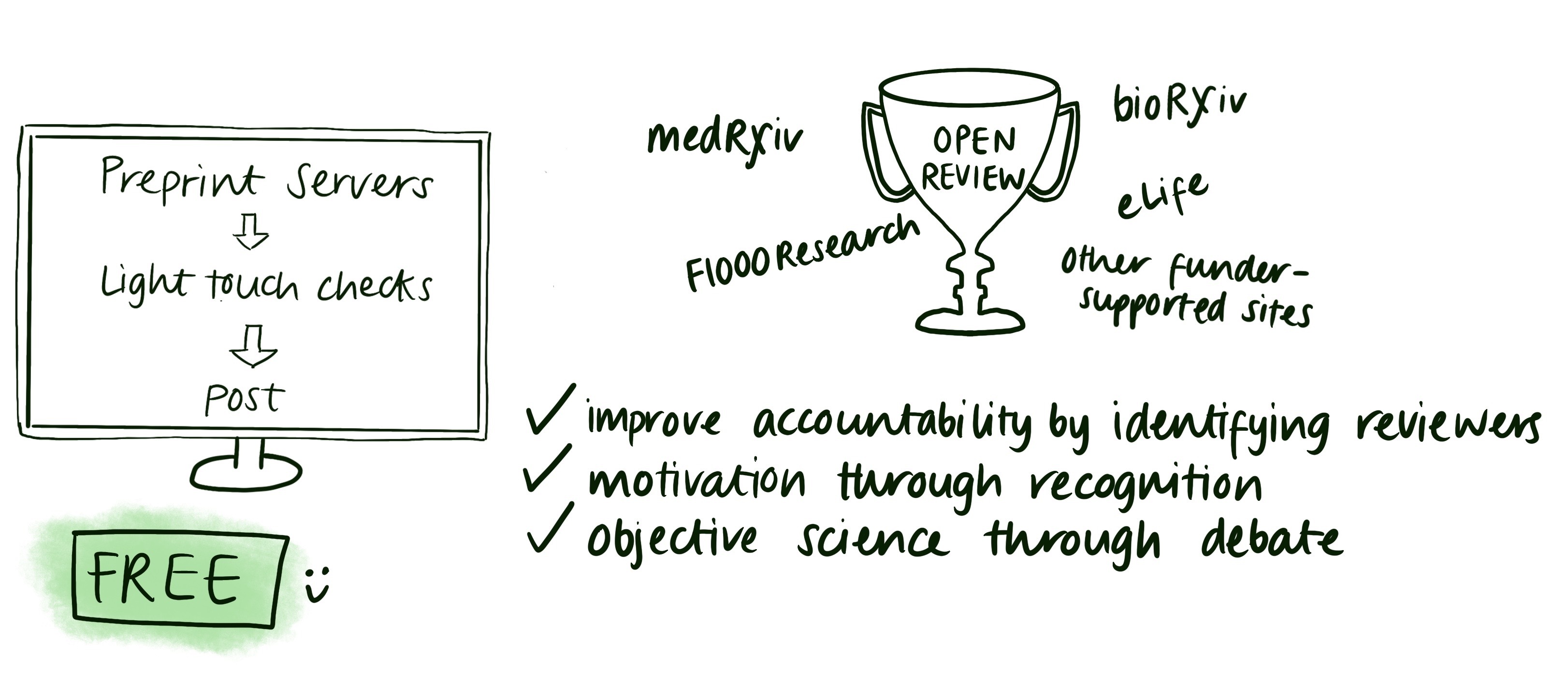

Rapidly increasing use of preprint servers bioRxiv and medRxiv, and innovative publishing models at eLife, F1000Research and elsewhere is moving inexorably to a world of post-publication review. The delays and expense of traditional reviewing are harder than ever to justify when there is an instant and low-cost alternative.

Is open review the solution?

Open reviewing means publishing reviews, even reviewer names, alongside a paper. If reviewers are hard to find, wouldn’t ECRs being reluctant to criticise a senior scientist’s work increase the problem? Not necessarily – the exact opposite can be true. Becoming part of constructive scientific debate is a great way for an ECR to demonstrate their maturity as a scientist. If you remember conferences at all by now, you know this from Q&A sessions. It could even rank alongside publications in those all-important fellowship and recruitment decisions.

Whatever the route forward, peer review has to change. What should be a vital contribution to the research community is neglected. It can feel like free labour for profit-making journals; no-one even knows you do it, and there is no career recognition. There is also no accountability. When just reviewer and editor know who reviewed, it is all too easy for subjective, unsubstantiated comments to go unchallenged.

What can you do?

Change is always difficult. Even Michael Eisen, pioneer of Open Access publishing at PLoS and open reviewing at eLife, had to compromise on his aim of revolutionary change. But as Amazon, Netflix, Zoom and (apparently!) Tinder have shown, change becomes inevitable when the right platform meets enough willing users. Preprint servers are free to use, quick, and already where the action is. Once we all see this, and transparent reviewing ensures that everyone contributes, it is hard to see any other model competing.

The future of peer review is in our hands. Each of us can influence it by posting our work as preprints and by contributing to, even prioritising post-publication reviews. Those of us who have done well in the current system, for all its flaws, owe it to the next generation of researchers – our postdocs and students – to leave it better than we found it.