Written by Prof. Michael Coleman (University of Cambridge)

Illustrated by Dr. Alice White (freelance science illustrator) and chimpmanagement.com

They’re some of the biggest questions in science: can you succeed without becoming cold, calculating and ruthless? And also without damaging your relationships and health? Professor Steve Peters, author of the bestseller The Chimp Paradox gives us a manual to do just that in his new book, A Path Through the Jungle*.

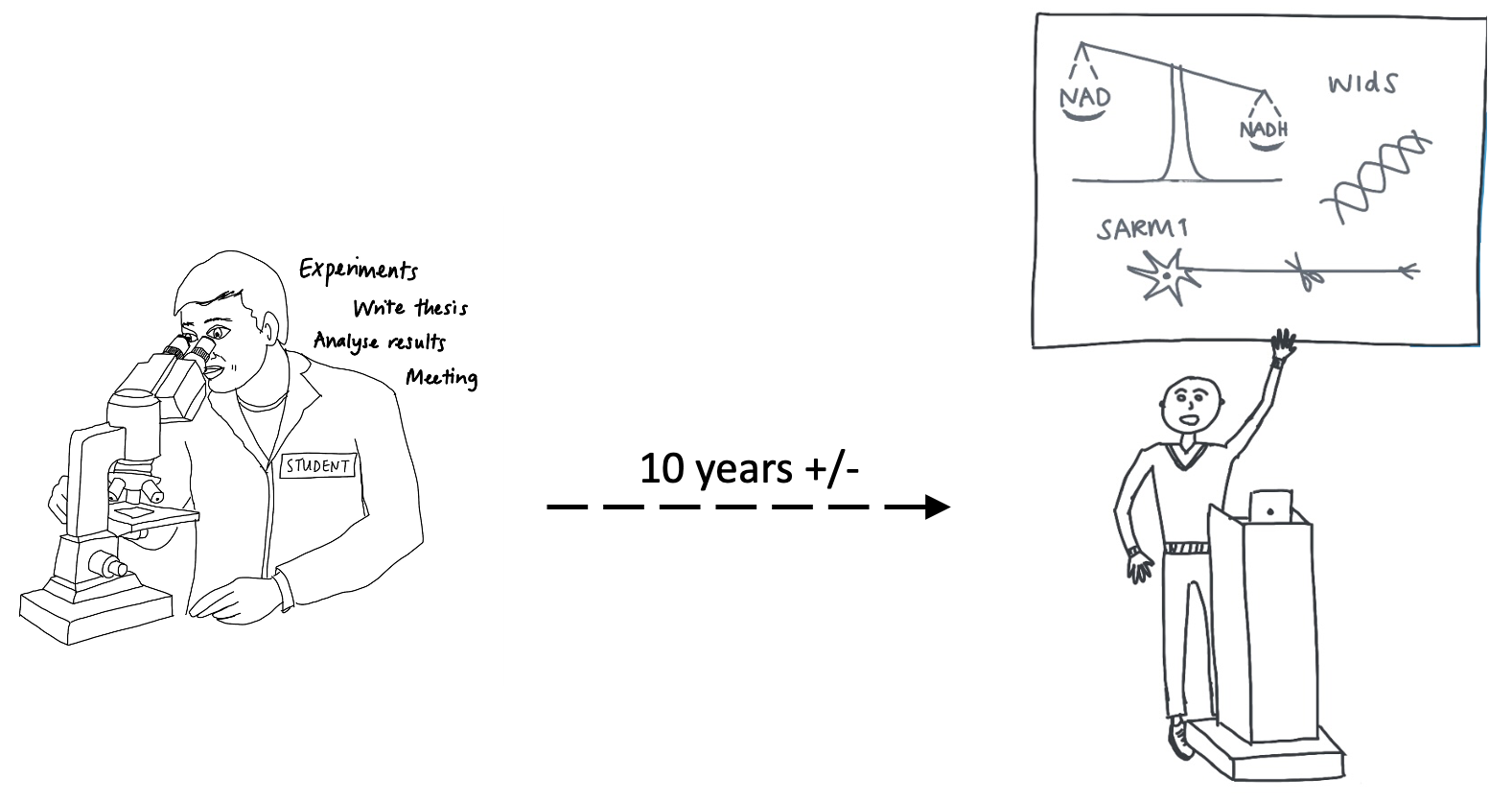

The book wasn’t written for scientists any more than anyone else. But whether you’re a graduate student, an Early Career Researcher or a seasoned PI, its content could profoundly enhance your performance and career satisfaction. Its origins lie in Peters’ work with medical students, mental health patients and psychopaths. Its full power became apparent in the world’s top cyclists, and in snooker, soccer and martial arts. Its versatility has been tested with nurses, teachers and trainee soldiers. Its central message is that whatever our roles in life, our effectiveness, satisfaction and happiness depend on recognising what we really want and using these methods to avoid being derailed along the way.

And crucially, what we really want may not be as obvious as we think...

*A few complimentary tickets are available for Professor Steve Peters’ keynote presentation ‘Neuroscience of the mind applied to everyday life’. University of Derby, 5-7pm, 2nd November 2022. Contact: bev@chimpmanagement.com

Stop and think for a moment. Find a quiet spot. Take six deep breaths and relax before reading on.

What really brought you into scientific research? Was it a desire to make a difference? A need to understand? A family illness you wanted to solve? The enjoyment of doing something you were good at? Prestige? Pleasing your parents? You needed a job?

Whatever your answer, somewhere deep down there is an emotional foundation: curiosity, achievement, family bonds, or the simple fear of being unemployed.

So here’s the irony: your emotions brought you here but what you need to do good science is a rational mind!

The book begins with a brilliantly communicated and illustrated lay summary of brain regions responsible for our emotions (the limbic system) and rational thought (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; DLPFC). Peters calls these the ‘Chimp’ and ‘Human’ respectively, as our emotional brain broadly resembles that of our nearest evolutionary relatives, but our DLPFC is substantially more complex than theirs. Your Human, he says, is the ‘real you’ – the part that understands what you really want. But your Chimp is faster and more powerful. If it were not, you wouldn’t be here. Our ancestors would have been eaten, killed by another tribe, or failed to reproduce. The genes driving our emotions today are those we inherited from the ‘winners’ in those jungle days. Already, our illogical society today makes more sense!

But wait! We’re scientists. We can be rational, can’t we? Well, not exactly, at least not as much as we think. On reading the book the lightbulb moment for me was this quote in Unit 2: “The first thing your Chimp does [on receiving new information] is to stop your Human from acting”. So trigger your emotions, and goodbye rational thought!

How many of the following have you experienced? You feel too intimidated to speak up in a meeting, or ask a question at a conference, despite knowing you have something valuable to add. You’re overwhelmed and you can’t focus. A career-threatening grant, fellowship, paper or job rejection leaves you unable to concentrate on the next experiment or paper no matter how much you try. You sense someone taking credit for your idea and you’re so consumed with rage you can think of nothing else. A hypothesis you’ve been testing for years turns out to be wrong, and it takes weeks of despair about your ‘wasted life’ before you spot the much better, and ultimately correct hypothesis. And perhaps most insidious of all, where we so often deceive ourselves, we lack the courage to challenge the status quo, as scientists must, because our need for career security forces us to ‘fit in’?

Where is our rational mind in these moments? Silent! Our greatest ability: inaccessible! How can we do our work without the primary tool of our trade? If positive emotions brought us into science, will it be this bag of negative emotions – the career insecurity, the pain of rejection, raging injustice, jealousy – that limits us, or even drives us out? Or is there a better way to handle them?

Enter the concept of ‘Chimp Management’. Five Units of the book, ‘Developing Yourself’, ‘Managing Emotional Reactions’, ‘Your Mind in Harmony’, How to Nurture your Chimp’ and ‘Managing your Drives’, weave well-established concepts of performance enhancement and psychotherapy with Peters’ unique and powerful metaphor of the Chimp that shares our lives. You can’t ignore it, you can’t defeat it, you can’t reason with it. And nor should you try, because ironically your Chimp is also your best friend (the meaning of ‘Chimp Paradox’). That excitement you felt after a nice result, which brought you the energy for a burst of experiments to finalise your career-making paper – that’s your Chimp too! But you can, and must, manage it, for your own sake and out of responsibility to your colleagues. Anyone who has trained a dog knows how this is done, but the animal in our own heads is harder to spot. These five Units tell us how it is managed.

But emotional messages are complex. They are not always what they seem and what they are telling you can be particularly unclear (Units 8-10). Although you can’t reason with your Chimp, you can ‘talk to it in its own language’, that of emotions: the messy stuff scientists usually don’t like! The key to stopping what Peters calls ‘Chimp hijacks’ (like those three paragraphs above) is to reprogramme the third major functional unit in our brains – the ‘Computer’ (the hippocampus, amygdala and other areas). Stored in these areas is a huge amount of useful knowledge and habits (our ‘Autopilots’), positive and negative emotional memories, and beliefs and habits from early life, some of which no longer serve us (‘Gremlins’ and ‘Goblins’). Reprogramming the unhelpful parts takes time and a lot of reflection and repetition. But just as we can learn to play a musical instrument or drive a car, we can get there with commitment, practice, and noticing signs of progress.

In this way, destructive habits we naively think we can change by willpower every New Year can gradually change. We can find new ways to handle problems both inside and outside work, from a dropped sample to realising we got our favourite hypothesis wrong or our grant/fellowship being rejected. Our Computers store our personal truths, perspectives and values, which enable us to accept these and move on. But occasionally, when things are really tough, the unconditional support of our ‘Troop’ (our closest friends or family) is essential. So next time we neglect work-life balance, consider how vulnerable we leave ourselves if we end up without that safety net. How futile can it be to continue working so hard with an unsettled Chimp in our heads?

Units 18-21 deal with acute and chronic stress, choosing the right environment to maximise performance, satisfaction and happiness (‘The right part of the jungle’), and the importance of self-care to keep this sustainable. When we choose a new workplace, it’s important to ask whether the potential colleagues there, and particularly those at the top, share our values. Without that, we are lining ourselves up for stress and poor performance, however hard we work.

And finally – the big hurdle for many scientists – Peters helps us optimise our interactions with others with a new, intriguingly scientific view of this basic life skill. Many of us enter science because we are more at ease, and perhaps better, at handling experiments than messy things like other people. I certainly did. After a few iterations we perfect our experiments and get reproducible results. In contrast, other people will always remain unpredictable and beyond our control. But as in any career if we progress, handling people eventually becomes the core of our job. Getting the best from them becomes the limiting factor. We need to recruit, train, supervise and help motivate excellent colleagues; we need to pitch for money, or a job, to groups of relative strangers; we need to engage the audience at a conference; and we need to establish productive collaborations based on trust and respect, not just complementary skills. But these can be a challenge when the main reason we progress is because we were good at experiments.

On this point, the book brings its most brilliant insight of all: everyone has a Chimp, not just us! That colleague we are furious with, that frowning panel member in a fellowship interview, that nervous applicant for our studentship, that collaborator who wants to be first author, and that person at a conference we didn’t dare to speak to: they have Chimps too. They too may not be acting how they truly want but how their emotions ‘tell’ them to. The key to accessing their logic is to relax their Chimp: relax yourself, seek to understand not impress, question your expectations of them, and use all the nonverbal and verbal tools available to convey psychological safety. If we can do even some of this, there is a whole new world waiting to be discovered.

This book will appeal to a wide range of scientists, and especially neuroscientists. It is based in the sciences of evolution, neurochemistry, activity-driven neuroplasticity, and brain imaging; it cites 472 original publications, from which I can confirm the accuracy of the dozen I checked and the parts I knew already; and it speaks to many of the major challenges scientists face, not least the need to understand our own minds as well as our experiments. It connects the knowledge we learn in our day jobs with everything that matters to us, at home and at work. And it is one of the best examples I’ve seen of communicating science to the public.

Inevitably, the price of communicating key principles to all with such an effective model is that some experts may feel it simplifies too much. Peters acknowledges this but what matters is the model’s usefulness in everyday life, and for us the way it connects with excellent science, even if not every detail. The differences between real Chimp and Human brains are not so black and white. The brain has other functions too. And developmental or neurodegenerative disorders in some people interfere with how one or more of their Chimp, Human, or Computer works.

The model is not effective for everyone. Using it requires commitment, hard work and a belief that it is worth it. But for those can do this, it can have tremendous value. A Path Through the Jungle can help us define our personal meaning of ‘success’ and give us the best chance of reaching it, without sacrificing our values, our emotions, our health, our relationships, or the culture of our workplace. The answer to the questions posed at the start is a definite yes!