By Ella Hopkins

After the success of my previous blog post on how the coronavirus makes us ill, I have decided to continue on the theme of explaining a coronavirus concept at increasing levels of difficulty.

From now on, the coronavirus will be referred to as SARS-CoV-2 and the disease that SARS-CoV-2 causes will be referred to as COVID-19, so as not to confuse it with other coronaviruses. Specifics on SARS-CoV-2 testing that are different to standard qRT-PCR testing is not currently widely circulated online, so if there are any errors, please leave a comment and I can edit the article. Furthermore, I am hoping to start working in COVID-19 testing shortly, so anything I learn on the job can be used to update the article accordingly.

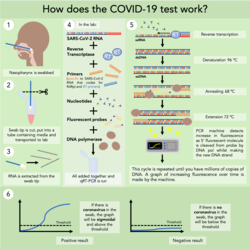

In the UK, only people admitted to hospital with symptoms of COVID-19 and some medical professionals are currently being tested. The first step involves running a swab along the nasal cavity until it reaches the nasopharynx. When removed, the tip of the swab is cut off with scissors and put in a vial containing ‘liquid transport media’ and sent to a testing lab.

In the lab, the vial is vortexed to ensure that any viral RNA is contained within the media rather than the swab, and the RNA (should there be any) is extracted using a standard RNA extraction kit.

The specific PCR test that the NHS is using is a one-step qRT-PCR test. For those not familiar with the basics of PCR, I recommend looking at this graphic (on Twitter) before continuing. RNA cannot be directly amplified in PCR, so in some PCR tests, the RNA is converted to cDNA before the PCR being done (two-step PCR). However, I assume to speed up testing, one-step qRT-PCR is being done, where the RNA is converted into cDNA in the same step that the DNA is being amplified.

The exact components put into each test varies between companies. These are the NHS’s and the WHO’s recommended master mixes. Importantly, they contain primers specific to SARS-Cov-2 RNA that codes for the RdRp gene (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase).

qRT-PCR comprises 4 main steps. The first is the production of cDNA from RNA by reverse transcriptase enzyme. RT primers bind the RNA and reverse transcriptase uses the RNA as a template to make a new strand using free nucleotides. Then the following steps are standard in PCR; melting the cDNA to two single strands at the 96 °C denaturing stage, the primers binding the ssDNA at the 68 °C annealing stage, and the DNA polymerase making a new strand of DNA complementary to the template strand using the free nucleotides at the 72 °C elongation stage.

The test kits used by the NHS use fluorescent probes to detect the increase in DNA strands as the cycles are repeated. These probes have a 5’ fluorescent molecule and a 3’ quenching molecule; when both are present on the probe no fluorescence is given off. They bind to the ssDNA template strand in the annealing stage. The DNA polymerase cleaves the 5’ fluorescent molecule when it reaches the point on the template strand that the probe is bound, releasing the fluorescent molecule away from the quenching molecule, to fluoresce brightly. This increase in fluorescence is therefore directly correlated to the increase in DNA, and is detected by the machine. Once the increase in fluorescence has gone above the threshold level, it can be said that the result is positive and there is SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the swab.

Before the test can be given back to the doctor that requested the test, the controls also need to be checked, to make sure the test ran normally. There are positive and negative controls included in the SARS-CoV-2 test kit to ensure that no false positives or false negatives are reported. These include a positive control of SARS-CoV-2 RNA made in vitro and supplied by the kit. Negative controls for both the extraction stage and for the amplification step are also included.

Whilst these controls reduce the number of false positives and negatives, there has been anecdotal evidence that the test will report patients as negative multiple times and only give positive results much later in the infection time course. It remains to be seen whether this is the fault of the test itself, or the virus not colonising the nasopharynx but still wreaking havoc elsewhere in the body.

Also, it is important to make sure that the swab is not contaminated with SARS-CoV-2 from other sources at any point as this could lead to false positives. People not displaying symptoms could still be infectious, so it is vital that all healthcare workers and scientists running the test wear adequate PPE.